I often receive questions about the terms Top, Mid, and Base notes in perfumery, as they tend to create confusion in modern practices. In the past, perfumers adhered to a classic pyramid structure, without relying on the extensive use of “linear” aroma chemicals that characterize today’s creations. So, in this post, I’ll help clarify these concepts.

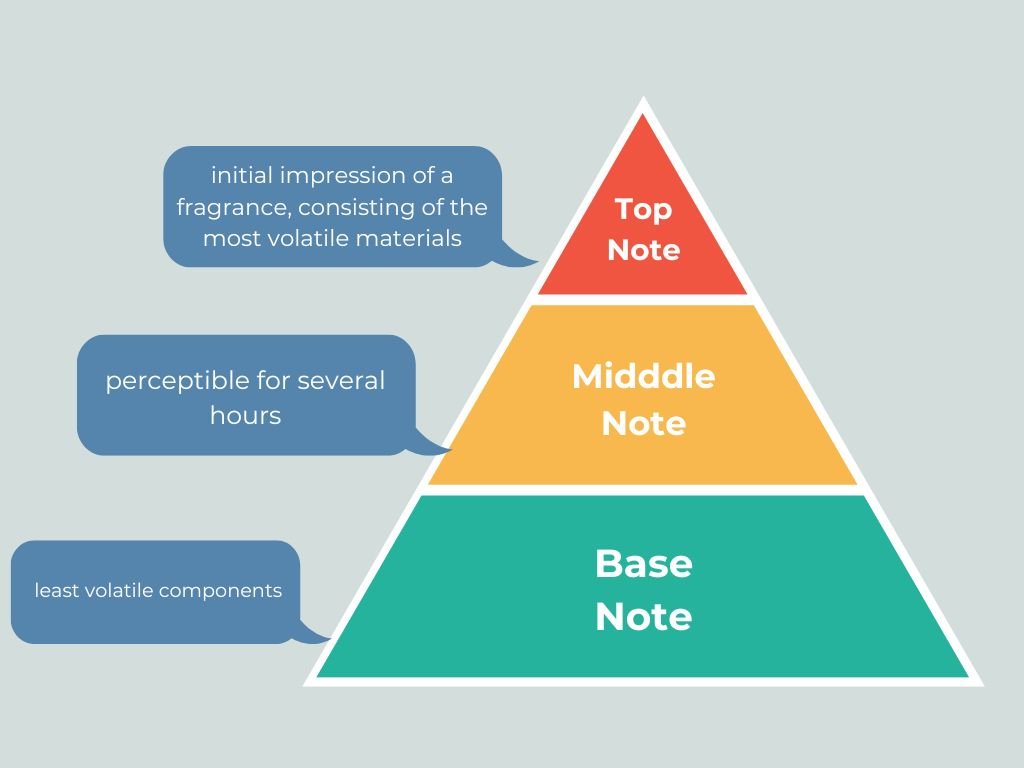

A straightforward way to describe top, middle, and base notes is as follows:

Below is the simplest guide to notes. You may also check out our guide bout citrus notes here.

1. Top Notes

Usually, these descriptions are used alongside a pyramid diagram as an illustration which can be a bit misleading as we don’t really smell perfume in this way.

Top notes are the initial impression of a fragrance, consisting of the most volatile materials, which means they evaporate the quickest. Typically, these include bergamot, lemon, and other citrus oils, as well as lavender, neroli, and some spicy elements like coriander and cardamom.

2. Middle Notes

Middle notes, or the heart of the fragrance, become prominent after the top notes fade and are perceptible for several hours. These often include floral scents such as rose, geranium, ylang, and jasmine.

3. Base Notes

Base notes are what remain on the skin during the dry-down phase. As the least volatile components, they linger the longest when other notes have dissipated. These heavier resins, balsams, and woods, like benzoin, vanilla, and sandalwood, also help to anchor the fragrance on the skin.

A pyramid suggests that each material lifts off sequentially from top to base, but this isn’t the case. While the fragrance pyramid serves as a handy marketing tool, it can be misleading for perfumery students and create confusion. In practice, you’ll initially perceive mostly top notes, along with some middle and a hint of base notes. Over time, the scent evolves to reveal more middle and base notes, finally settling into the base, known as the drydown. When categorizing materials as top, mid, or base notes, flexibility is essential, especially given the variability in natural materials, therefore, the pyramid should be viewed as a loose guide rather than a strict framework. Additionally, the behavior of fragrance materials in a perfume composition can differ slightly from when they are isolated.

Materials interact with one another, causing some top notes to be subdued while base notes may be more prominent than if they stood alone. In today’s commercial perfumery, fragrance structures often lean towards linearity, frequently featuring significant amounts of high-impact aroma chemicals. Consequently, the initial notes you perceive are not always the top notes. This shift renders the traditional fragrance pyramid somewhat obsolete, prompting the need for alternative methods to illustrate composition.